Of Water, Air, Earth Fire and Other Romanticism

Thinking of Schumann and Chopin

Annely Zeni

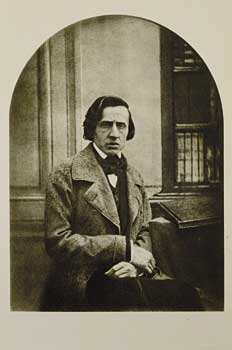

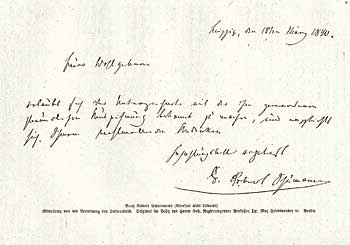

1810: what do the Pole – born in the almost unpronounceable suburb of Zelazowa Wola – Frederyck Chopin, and the German – born in the medieval city of Zwickau – Robert Schumann, have in common in addition to their birth year? Certainly, the fascinating cultural season of Leopardi and Schopenauer, Holderlin and Keats, Novalis and Wordsworth, Blake and Turner, Hugo and Byron, Gericault and Shelley, an ideal artistic community that the well-read Schumann imaginatively represented in the League of Brothers of David, defenders, in word and music, of the new romantic language, while the less cultured Chopin (who preferred to answer letters with musical pieces) lived directly in the gentle French countryside of Nohant alongside the strong-willed George Sand, the controversial and passionately independent writer who loved to surround herself with the most anti-conformist and revolutionary French intellectuals. It is difficult to imagine today that the melodies of the Nocturnes or the Raft of the Medusa belong to the well-known, or better to the consummate “subversive” and “grass-roots” charge of Romanticism embraced by the enthusiasm of twenty-year-old intellectuals: “Oh youths, you have a long and difficult road before you: a strange tint of red hovers in the sky, 1810: what do the Pole – born in the almost unpronounceable suburb of Zelazowa Wola – Frederyck Chopin, and the German – born in the medieval city of Zwickau – Robert Schumann, have in common in addition to their birth year? Certainly, the fascinating cultural season of Leopardi and Schopenauer, Holderlin and Keats, Novalis and Wordsworth, Blake and Turner, Hugo and Byron, Gericault and Shelley, an ideal artistic community that the well-read Schumann imaginatively represented in the League of Brothers of David, defenders, in word and music, of the new romantic language, while the less cultured Chopin (who preferred to answer letters with musical pieces) lived directly in the gentle French countryside of Nohant alongside the strong-willed George Sand, the controversial and passionately independent writer who loved to surround herself with the most anti-conformist and revolutionary French intellectuals. It is difficult to imagine today that the melodies of the Nocturnes or the Raft of the Medusa belong to the well-known, or better to the consummate “subversive” and “grass-roots” charge of Romanticism embraced by the enthusiasm of twenty-year-old intellectuals: “Oh youths, you have a long and difficult road before you: a strange tint of red hovers in the sky,  I know not whether of dusk or dawn. Make it become light,” exhorted Master Raro through the mouth of the exuberant Florestan, to remain with the Schumann's symbolic creations. A world that attributed to emotion – a strange tint of red – the imperious force of total passion, both amorous and political, coincident with creativity itself, blind and uncontrollable, in a disquieting contradiction between desire of life and anxiety of death: thus, the typical image of the romantic artist melts and confuses the earthly drama of Chopin and Schumann, both marked by physical and psychic fragility, both destined to die prematurely (1849 and 1856) and, cynically, of “fashionable” diseases: tuberculosis, emblematic of the consumption of the life force in the tension towards the infinite and madness, a status symbol of a truth located beyond the limits of reason. I know not whether of dusk or dawn. Make it become light,” exhorted Master Raro through the mouth of the exuberant Florestan, to remain with the Schumann's symbolic creations. A world that attributed to emotion – a strange tint of red – the imperious force of total passion, both amorous and political, coincident with creativity itself, blind and uncontrollable, in a disquieting contradiction between desire of life and anxiety of death: thus, the typical image of the romantic artist melts and confuses the earthly drama of Chopin and Schumann, both marked by physical and psychic fragility, both destined to die prematurely (1849 and 1856) and, cynically, of “fashionable” diseases: tuberculosis, emblematic of the consumption of the life force in the tension towards the infinite and madness, a status symbol of a truth located beyond the limits of reason.  But apart from the cliché of genius and intemperance, of artistic sehnsucht (longing) and daily misery, apart from the romanticism of Clara and George, the diabolic coincidences between art and life, Schumann and Chopin share that attitude of relentless research and experimentation into the new that places the genius's most authentic nature in the spirit of the avant-garde. One might recall – not without an unfair blow to the topos of the divine inspiration of the creator between one exhaustion and another – the painstaking work of Chopin – who, romantically described by Sand, closed himself in a room and – according to her – “crying and raving” worked for days and days on the few bars of a prelude – or the intense work of Schumann, for example, in symphonic expression, seeking alternative paths to escape the overhanging shadow of Beethoven. So, the method that exited through the window of illuminism, comes in through the door of romanticism and defines precise strategies for both: in the case of Schumann, renewal passes through descriptive, extra-musical elements that modulate the form in a narrative dimensions and, at least apparently, concretely imaginative. For Chopin, on the other hand, it seems that the avant-garde impulse must be contained within forms that were traditional, Sonata, Etude, the very Nocturne (which had the precedent of the Irishman Field) if not actually 18th-century, such as the prelude, which, resisting a descriptive intention, were deliberately abstract. But apart from the cliché of genius and intemperance, of artistic sehnsucht (longing) and daily misery, apart from the romanticism of Clara and George, the diabolic coincidences between art and life, Schumann and Chopin share that attitude of relentless research and experimentation into the new that places the genius's most authentic nature in the spirit of the avant-garde. One might recall – not without an unfair blow to the topos of the divine inspiration of the creator between one exhaustion and another – the painstaking work of Chopin – who, romantically described by Sand, closed himself in a room and – according to her – “crying and raving” worked for days and days on the few bars of a prelude – or the intense work of Schumann, for example, in symphonic expression, seeking alternative paths to escape the overhanging shadow of Beethoven. So, the method that exited through the window of illuminism, comes in through the door of romanticism and defines precise strategies for both: in the case of Schumann, renewal passes through descriptive, extra-musical elements that modulate the form in a narrative dimensions and, at least apparently, concretely imaginative. For Chopin, on the other hand, it seems that the avant-garde impulse must be contained within forms that were traditional, Sonata, Etude, the very Nocturne (which had the precedent of the Irishman Field) if not actually 18th-century, such as the prelude, which, resisting a descriptive intention, were deliberately abstract.

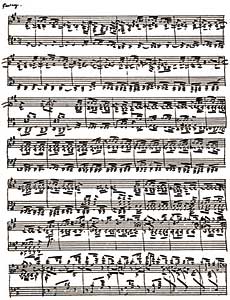

With the intention of restricting the visual field to a “romantic heart” which beats in favour of prince piano – more for Schumann, naturally, because Chopin composed exclusively for his beloved keyboard – the ensemble of the two piano catalogues reveals a sympathetic dedication to short pieces – better suited to the lightning speed of emotion without development – which the method organises cyclically, nevertheless. Thus, the articulation of the form puts subtle, intellectual artifice back in play, which can be verified by considering, here, two famous piano cycles such as the Carnival opus 9 by Schumann and the Etudes opus 10 by Chopin. Bach's riddle of the sphinx (i.e., the letters of the surname Schumann corresponding to musical notes, “asch-scha” A, E-flat, C and B) makes a net of connections between the single miniatures, while the choice of tonalities, the distribution of the agogics, the characteristics of the piano technique indicated from time to time, correspond to a precise plan in Chopin's etudes. But, in the end, the expressive results overturns the objectives in a sort of rhetorical chiasmus, for which the abstract Chopin assumes descriptive tints while the descriptive Schumann can't help but be philosophically German. With the intention of restricting the visual field to a “romantic heart” which beats in favour of prince piano – more for Schumann, naturally, because Chopin composed exclusively for his beloved keyboard – the ensemble of the two piano catalogues reveals a sympathetic dedication to short pieces – better suited to the lightning speed of emotion without development – which the method organises cyclically, nevertheless. Thus, the articulation of the form puts subtle, intellectual artifice back in play, which can be verified by considering, here, two famous piano cycles such as the Carnival opus 9 by Schumann and the Etudes opus 10 by Chopin. Bach's riddle of the sphinx (i.e., the letters of the surname Schumann corresponding to musical notes, “asch-scha” A, E-flat, C and B) makes a net of connections between the single miniatures, while the choice of tonalities, the distribution of the agogics, the characteristics of the piano technique indicated from time to time, correspond to a precise plan in Chopin's etudes. But, in the end, the expressive results overturns the objectives in a sort of rhetorical chiasmus, for which the abstract Chopin assumes descriptive tints while the descriptive Schumann can't help but be philosophically German.  In fact, the faceted variety of the Carnival hides “the deepest meaning of existence, its constant becoming (the party), its multiplicity (the masks), human solitude (Aveu) the happy agreement that men can seek and find during the course of time, all characterised by a veiled nihilism” (G. Rausa). In the Etudes, on the other hand, the distillation of the technical element ends up alluding to a latent scenic principle, just as in painting, the background becomes the centre of attention: water runs in the arpeggios of the etude in A-flat, air lightly blows in the second number of the composition, earth expresses itself in the heavy material chords of the third and fire (Presto with fire is precisely the phrase) flames in the fourth: prophecy of a romantic sentiment that is dissolving itself in refined impressionist analogies. No long after, it will be the turn of Baudelaire's “living columns”. In fact, the faceted variety of the Carnival hides “the deepest meaning of existence, its constant becoming (the party), its multiplicity (the masks), human solitude (Aveu) the happy agreement that men can seek and find during the course of time, all characterised by a veiled nihilism” (G. Rausa). In the Etudes, on the other hand, the distillation of the technical element ends up alluding to a latent scenic principle, just as in painting, the background becomes the centre of attention: water runs in the arpeggios of the etude in A-flat, air lightly blows in the second number of the composition, earth expresses itself in the heavy material chords of the third and fire (Presto with fire is precisely the phrase) flames in the fourth: prophecy of a romantic sentiment that is dissolving itself in refined impressionist analogies. No long after, it will be the turn of Baudelaire's “living columns”.

|

NUMBER 9

NUMBER 9

NUMBER 9

NUMBER 9