For twenty years Papà Miguel Tovar had been running a small state lottery office in a square in the outskirts of Merida, where the clients could ponder and pick their lottery numbers in peace, before delivering their playing cards at the counter behind which Miguel was seated. If the weather was fine, Miguel Tovar would take out a little chair and sit opposite the state lottery office to chat with clients about issues relating to the general financial situation. He would sometimes also take out a little table, on which he would drink the beer that he had bought from the bar on the other side of the square, and from time to time he would also play some numbers, although he relied more on the gratitude of his clients, that is, on the fact that they would leave him a portion of each win as a sign of merit and thanks. The state lottery office was famous because nobody had ever won anything after playing there and this fame guaranteed him a sufficient number of clients to enable a modest and precarious existence. Exactly twenty years previously, having dedicated his time to gambling for a few months, Miguel had come to the conclusion that it would be impossible to win a sum that would allow him to live comfortably without some further study. One of the reasons was the impossibility of being able to establish the amount of such a sum, considering the variable nature of his needs, while the other reason was his supposed immortality; and so he decided to open a state lottery office. For twenty years Papà Miguel Tovar had been running a small state lottery office in a square in the outskirts of Merida, where the clients could ponder and pick their lottery numbers in peace, before delivering their playing cards at the counter behind which Miguel was seated. If the weather was fine, Miguel Tovar would take out a little chair and sit opposite the state lottery office to chat with clients about issues relating to the general financial situation. He would sometimes also take out a little table, on which he would drink the beer that he had bought from the bar on the other side of the square, and from time to time he would also play some numbers, although he relied more on the gratitude of his clients, that is, on the fact that they would leave him a portion of each win as a sign of merit and thanks. The state lottery office was famous because nobody had ever won anything after playing there and this fame guaranteed him a sufficient number of clients to enable a modest and precarious existence. Exactly twenty years previously, having dedicated his time to gambling for a few months, Miguel had come to the conclusion that it would be impossible to win a sum that would allow him to live comfortably without some further study. One of the reasons was the impossibility of being able to establish the amount of such a sum, considering the variable nature of his needs, while the other reason was his supposed immortality; and so he decided to open a state lottery office.

He had been earning his livelihood from this in a satisfactory manner for twenty years. After two heart attacks he had gradually resigned himself to the loss of his immortality, or at least, he had postponed a decision in this regard until to after his big win. The clients who came to play the lotto were all propertyless like him and so there was no possibility of him receiving a win or a quota from them. For all those years he had imagined the client who had the possibility of a more substantial win as a person with an elegant appearance, looking somewhat like a devil who would arrive to play his numbers shortly before closing time, and so as not to lose out, he would remain open well beyond midnight. But above all, throughout those twenty years, he had continued to study, to perfect and then to repudiate his own system for winning the lotto.

For a time he had formed an apparently strong friendship with a specialist in skin diseases, who, rather than curing his patients, would hypnotise them and try to get them to give him the lottery numbers. This method had proven successful: in the midst of their state of hypnosis, some of his patients were able to give him the numbers extracted in any past date, but however hard the dermatologist tried, they never went beyond the numbers that had just been drawn. In the end, the dermatologist had let things lie and he married a wealthy patient of his, whom he had treated with hypnosis for a non-existent rash. Shortly after his marriage, he had regretted his decision, given that his wife had opened a private practice for him and obliged him to work from morning until night only using hypnosis with the application of a very substantial fee; and so the dermatologist no longer had the possibility of  experimenting his research in the field of hypnosis and the lotto, which was no less attractive for him, despite the fact that he was now earning more that he would ever have been able to win. His dream, as soon as he had the time, was to recommence his studies on the relationship between hypnosis and the lotto, to win, and then get divorced. experimenting his research in the field of hypnosis and the lotto, which was no less attractive for him, despite the fact that he was now earning more that he would ever have been able to win. His dream, as soon as he had the time, was to recommence his studies on the relationship between hypnosis and the lotto, to win, and then get divorced.

Shortly afterwards, Papà Miguel lost his wife, subsequently also one of his sons and by now he only expected one thing from life: to have a share in the lotto jackpot. After dinner he would calculate the expected win or his relative quota and it often occurred that there was money left over and so, in a desperate state, he would buy everything possible, or on the contrary, there was no money left over; and so he would investigate how he could have made such a mistake in his purchases and he would strike things out reluctantly.

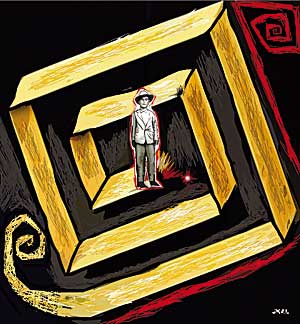

After the death of his wife, he had started to dedicate his time to a new passion: during the period in which the hurricanes prevented him from working, he took great pleasure in visiting various mazes and, with the excuse of having gotten lost, he would continue to wander around inside them, even after they had closed and the custodians of the maze would often find him there the day after, in a state of exhaustion. The last maze that he visited proved fatal, it was in the garden of the castle of the city of Dobříš. Despite the fact that he had quickly come out of it, unlike what he was used to doing, after five minutes, he returned to a world that was entirely different and unknown to him, in which he wandered until his tragic death. For him the past and the future had become entirely inverted. He could see, or rather, he could remember everything about his future, but at the same time he completely forgot all the memories of his past, being able to merely presume it; he dreamt about what had happened to him and he would wait interminably on a bench in the park in vain, impatient, until what was yet to happen would become his past. The present, that instant in which his past got lost, became a form of suffering for him, he experienced what he had known in the tiniest details for a long time and at the same time he knew that he was living that instant for the last time, he knew that he was inevitably losing it, that he would no longer remember it, if not like a possibility, which he would never be certain about whether or not it had actually happened. He could see, or rather, he could remember everything about his future, but at the same time he completely forgot all the memories of his past, being able to merely presume it; he dreamt about what had happened to him and he would wait interminably on a bench in the park in vain, impatient, until what was yet to happen would become his past. The present, that instant in which his past got lost, became a form of suffering for him, he experienced what he had known in the tiniest details for a long time and at the same time he knew that he was living that instant for the last time, he knew that he was inevitably losing it, that he would no longer remember it, if not like a possibility, which he would never be certain about whether or not it had actually happened.

During that time, Miguel had become friends with Don Carlos B.B. After his return to Salamanca, he had not managed to repair his affected past, events slipped through his fingers, they occurred without him being aware of them; often in Salamanca foreigners came and went without Don Carlos even knowing about their stay, and he was no longer even able to forecast something as simple as the weather. People began to make fun of him and Don Carlos lost his importance, the importance that he alone was aware of.

The friendship between Papà Miguel and Don Carlos had been apparently advantageous for both from the beginning. Miguel telepathically informed Don Carlos of what was about to happen in the future  and Don Carlos would take accurate notes of the memories of his friend on a calendar with removable pages, the torn pages of which he would post on to his new friend. But then, for some unknown reason, the reciprocal flow of information was interrupted, we can only presume that some of the pages had not reached the intended recipient and Miguel Tovar fell back into that uncertainty regarding his past. and Don Carlos would take accurate notes of the memories of his friend on a calendar with removable pages, the torn pages of which he would post on to his new friend. But then, for some unknown reason, the reciprocal flow of information was interrupted, we can only presume that some of the pages had not reached the intended recipient and Miguel Tovar fell back into that uncertainty regarding his past.

Miguel’s liberation arrived in the form of sclerosis: little by little he could no longer recall his future. Shortly before his tragic death, he had begun to forget what was going to happen and he started to obstinately play the lotto again, until one day he ended up under a moving car, because the only thing that he could remember was that something was waiting for him on the other side of the road. By chance, that was the day that he had finally attained the lotto win that he had waited for so much in the past, but that nevertheless, he would not have been able to enjoy.

J. Kalvellido illustrations |