| |

For author Rosetta Loi, the art of writing “enables you to regain things that seemed lost for ever”. That’s especially significant when the author in question is a little girl who has never experienced the things her stories are about, but who writes about situations she has only heard of from adults – perhaps her grandparents who tell her tales of things that happened to other people long, long ago.

Memory shapes our stories and allows us to recreate situations which happened in the far distant past and which can no longer be experienced in real life; that’sexactly why they are so fascinating, so filled  with emotion and the desire that things should not be forgotten. Things that often happen in different lands far distant from each other, yet which are very similar in the way they cope with life, deal with problems and use the gifts nature provides for our survival.In the sameness of regions scorched by the freezing cold, people react in the same way, sharing and employing the same tactics that allow them to stay in the place where they were born, to avoid having to leave for unknown, maybe even more hostile terrain than that of their native land.

In this story, every idea is a step back in time, a foot on the staircase of memory, so that we reach the top refreshed, more complete and ready for the adventure of life, a pattern that is eternally repeated in places thousands of miles apart.

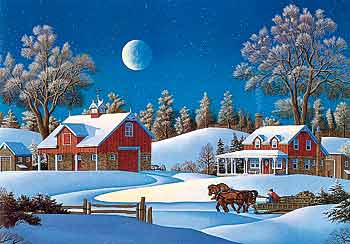

The biting cold nipped at Viljo’s cheeks as he tried with all his strength to split a birch log. It was tiring work and his toes felt frozen in their virsut, but he had to chop the wood that needed to be stored against the cold nights that would soon come. The axe blade was blunt, which certainly didn’t help and, already, after two hours’ work, Viljo felt ready for a rest. He loaded the pile of wood onto his sled and between the shafts, Rusko, his Finnish horse, neighed quietly. Viljo thought the horse needed a bit of hay too.

“Gee up, old lad, that’s it!” Viljo said encouragingly to Rusko, and off they set toward the village. The freezing wind made his eyes sting, but luckily there was a nice warm fur on the sled, the skin of a bear his big brother had killed long ago in the forest. White with snow, the forest looked beautiful and Viljo saw some deer stripping bark from the trees to eat. Life wasn’t easy for them either...

Soon he caught sight of the village and Rusko quickened his pace. A flock of crows was pecking at grain that someone had spilled. They took off, scattering in the air as the sled approached, but a moment later they were back at their fine banquet.“Here comes our young Viljo! He was bound to come back! We oldies knew he’d be coming”, said Grandpa Severi, who was sitting on a birch log by the fence at the side of the road. Viljo slowed Rusko and led him into the yard with the other horses. His neighbours, Kalle and Juho, the best bark cutters in the business, wearing their fur hats on their heads and their virsut on their feet, were busy stripping the bark from some logs. The aroma of korvike and pettuleipä drifted from the temporary cabin. In the yard, a group of men were skinning a freshly caught fox and hare, the rewards of a hunt in the forest. At the market next summer, along with dried pike, the skins would be much sought after, especially by foreigners. All sorts of people came to the market, even from the far-off South: dark-skinned men with spices and fabrics, merchandise the women all longed for. But summer was way, way off, and first everyone had to work hard. Another two loads of wood still had to be brought back today. With his stomach rumbling, Viljo went to get his dinner in the cabin, where Taavetti was already sitting chewing pettuleipä.

“So, Viljo’s decided to come into the warm and get something to eat. Hilma! Bring this young man a drop of korvike!” Taavetti called the serving girl and she ran over to serve Viljo. Viljo sipped his hot drink. It tasted bitter but times were hard and you had to make do with what there was. Taavetti passed Viljo the bread basket. There was still plenty of pettuleipä and Viljo gladly took some to fill his empty stomach. Pettuleipä didn’t give you much energy and it didn’t take away your hunger, but it was enough for now.

”How many loads of wood have you chopped today? Have we got enough puupäreet to see us through the dark nights?” Taavetti asked. ”How many loads of wood have you chopped today? Have we got enough puupäreet to see us through the dark nights?” Taavetti asked.

“There are plenty of puupäreet. There should be enough of those to give us light for six months, but this wood here is to keep the fire going more than anything”, Viljo answered, wolfing down his bread. Taavetti dropped his arm and smiled.

“Now I’ll have to hurry back to work. The mistress said there were two sacks of barley that need to be taken to the barn. I’ll have to be off. There’s work to be done...”When Wilhelmiina, the mistress of the house, lifted the lid of the vat to make butter the smell of sour milk overpowered the whole of the big kitchen. The soured milk had kept well and she could put it on the table for supper. The mushy porridge she had prepared was boiling on the stove. Three loaves of rye bread were lined up on the rail hanging from the ceiling and the toddler, a 2‑year old girl, had been put in the playpen to make sure she didn’t burn her fingers by touching the porridge: it was always her favourite food. The sokerisakset were on the table and beneath it sat the milk tub, which hadn’t been used for months, because the cows had stopped giving milk as soon as the first frosts arrived. That’s why the cows’ milk was soured, so that it would keep well and could be used later on. Above the fireplace hung the huge bread paddle and standing in the cutlery jar were the spoons belonging to everyone who lived in the house. The regular hum of the rukki came from the living room. Alli, the maid, was working with the last of the summer’s wool. First it had been combed into soft clouds ready for spinning. Alli was singing to herself: a soft, slow lullaby she had heard the mistress sing when she was rocking Liisa.

All the floors in the house were icy, except in the big kitchen, and you had to wear woollen socks if you didn’t want to catch a cold. Socks could only be made of wool and first the wool had to be combed and then spun and who would do the spinning and winding if there wasn’t a maid? Alli was happy to be able to help other people and to do work that was useful. That’s why she was always singing.

”Alli, Alli!” Alli heard the mistress calling her from the big kitchen.

Alli stood up, left the spindle where it was and made her way to the kitchen.“Go and fetch Viljo from the forest. He’s already done enough for a boy of seventeen.” Alli nodded, put a lightweight jacket over her shoulders, pulled back the bolt and stepped doggedly out into the cold.

This story is part of a book called “Nuove storie per antiche leggende” (New stories from old legends), the result of a co-operative project between Italy and Finland. The purpose of the joint effort is to encourage exchanges between the two countries in various fields of cultural interest and, in particular, to promote the specific nature of each land, from rediscovering cultural roots to taking a new look at old legends.

In this story we find objects and foods that are very similar to those that formerly used in the Italian valleys and which human ingenuity has invented, as if with a single brain, in order to cope with nature that is often harsh, but always the mistress of our lives.

Virsut: birch bark shoes stuffed with hay to keep out the cold.

Petuleipä: bread made with pinewood “sawdust”, that is to say, the “floury” wood between the bark and the inner trunk. Rye bread was made in round loaves with a hole in the middle so that it could be put on a stick and hung from the ceiling. This allowed it to dry, gave it a certain wholesome quality and kept it well out of reach of animals.

In the Trentino region too, bread for the poorer classes used a mixture of different types of flour made from beans, chestnuts, oats, rye, millet and, at the worst times of famine, acorns or the “sawdust” from young pine trees.

Korvike: coffee substitute. The poorest people could not afford to buy coffee so they used local plants from the woods and fields to make a hot, reviving drink. Chicory roots were dried, toasted and then ground to make “coffee”.In the mountains of the Trentino region, a very similar process was used to produce the barley coffee which, with bread and milk, made up the traditional breakfast. Toasting the “coffee” was almost a daily ritual, carried out at the fireside, slowly turning the toasting pan over the hot ashes.

Puupaäret: tapers. At a time when light wasn’t taken for granted, people made thin wooden sticks called ‘tapers’ which, when lit, burned slowly providing a weak indoor light.

Sokerisakset: sugar nippers. Sugar was a highly prized commodity and was often sold in loaves. Special “sugar nippers” were used to pinch off small quantities at a time.

Rukki:spinning wheel or winding machine. Either a machine used to spin wool into yarn or one to wind the spun yarn; both were in common use throughout the Alpine region. Rukki:spinning wheel or winding machine. Either a machine used to spin wool into yarn or one to wind the spun yarn; both were in common use throughout the Alpine region.

|

|